(Adding categories) |

(Removed excessive content in order to keep information concise) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Clr}} |

||

| − | [[File:Recycle.jpg|thumb]] |

||

| + | '''Recycling''' is the reprocessing of old materials into new products, with the aims of preventing the waste of potentially useful materials, reducing the consumption of fresh raw materials, reducing Energy consumed in conventional waste disposal. The overall result is a lowering of Greenhouse gases. |

||

| + | These materials are either brought to a collection center or picked-up from the curbside; and sorted , cleaned and reprocessed into new products bound for manufacturing. |

||

| − | '''Recycling''' is the process and processing used [[material]]s ([[waste]]) into new products to prevent waste of potentially useful materials, reduce the consumption of fresh raw materials, reduce [[energy]] usage, [[reduce]] [[air pollution]] (from [[incineration]]) and [[water pollution]] (from [[landfilling]]) by reducing the need for "conventional" waste disposal, and lower [[greenhouse gas]] emissions as compared to virgin production.<ref>{{cite web |

||

| − | | url=http://www.letsrecycle.com/do/ecco.py/view_item?listid=37&listcatid=231&listitemid=8155§ion=legislation |

||

| − | | title=PM's advisor hails recycling as climate change action.| publisher=Letsrecycle.com |

||

| − | | date=2006-11-08 |

||

| − | | accessdate=2010_06-19}}</ref><ref name="gar"/> Recycling is a key component of modern waste reduction and is the third component of the "[[Waste minimisation|Reduce]], [[Reuse]], Recycle" [[waste hierarchy]]. |

||

| − | There are some [[ISO]] standards relating to recycling such as ISO 15270:2008 for plastics waste and [[ISO 14001]]:2004 for environmental management control of recycling practice. |

||

| − | |||

| − | Recyclable materials include many kinds of [[glass]], [[paper]], [[metal]], [[plastic]], [[textile]]s, and [[electronics]]. Although similar in effect, the [[composting]] or other [[reuse]] of [[biodegradable waste]] – such as [[food waste|food]] or [[Green waste|garden waste]] – is not typically considered recycling.<ref name="gar">{{cite book | last = The League of Women Voters | title = The Garbage Primer | publisher = Lyons & Burford | year = 1993 | location = New York | pages = 35–72 | isbn = 1558218507}}</ref> Materials to be recycled are either brought to a collection center or picked up from the curbside, then sorted, cleaned, and reprocessed into new materials bound for manufacturing. |

||

| − | |||

| − | In the strictest sense, recycling of a material would produce a fresh supply of the same material—for example, used office [[paper]] would be converted into new office paper, or used [[polystyrene|foamed polystyrene]] into new polystyrene. However, this is often difficult or too expensive (compared with producing the same product from raw materials or other sources), so "recycling" of many products or materials involves their '''[[reuse]]''' in producing different materials (e.g., [[paperboard]]) instead. Another form of recycling is the '''[[wiktionary:Salvage|salvage]]''' of certain materials from complex products, either due to their intrinsic value (e.g., [[lead]] from [[battery (electricity)|car batteries]], or [[gold]] from [[computer]] components), or due to their hazardous nature (e.g., removal and reuse of [[mercury (element)|mercury]] from various items). |

||

| − | |||

| − | Critics dispute the net economic and environmental benefits of recycling over its costs, and suggest that proponents of recycling often make matters worse and suffer from [[confirmation bias]]. Specifically, critics argue that the [[costs]] and [[energy]] used in collection and transportation detract from (and outweigh) the costs and energy saved in the production process; also that the jobs produced by the recycling industry can be a poor trade for the jobs lost in logging, mining, and other industries associated with virgin production; and that materials such as paper pulp can only be recycled a few times before material degradation prevents further recycling. Proponents of recycling dispute each of these claims, and the validity of arguments from both sides has led to enduring controversy. |

||

| + | To judge the environmental benefits of recycling, the cost of this entire process must be compared to the cost of virgin extraction. In order for recycling to be economically viable, there usually must be a steady supply of recyclates and constant demand for the reprocessed goods; both of which can be stimulated through government Legislation. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| + | Recycling has been a common practice for most of human history, with recorded advocates as far back as Plato in 400 BC. During periods when resources were scarce, archaeological studies of ancient waste dumps show less household waste (such as ash, broken tools and pottery)—implying more waste was being recycled in the absence of new material. |

||

| − | ===Origins=== |

||

| − | Recycling has been a common practice for most of human history, with recorded advocates as far back as [[Plato]] in 400 BC. During periods when resources were scarce, archaeological studies of ancient waste dumps show less household waste (such as ash, broken tools and pottery)—implying more waste was being recycled in the absence of new material.<ref name="guide">{{Cite book | last = Black Dog Publishing | publisher = Black Dog Publishing | year = 2006 | location = London, UK | isbn = 1904772366 | title = Recycle : a source book}}</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | In [[pre-industrial]] times, there is evidence of scrap bronze and other metals being collected in Europe and melted down for perpetual reuse.<ref name="economisttruth"/> In Britain dust and ash from wood and coal fires was collected by '[[Waste collector|dustmen]]' and [[downcycling|downcycled]] as a base material used in brick making. The main driver for these types of recycling was the economic advantage of obtaining recycled feedstock instead of acquiring virgin material, as well as a lack of public waste removal in ever more densely populated areas.<ref name="guide"/> In 1813, [[Benjamin Law]] developed the process of turning rags into '[[shoddy]]' and '[[Glossary of textile manufacturing#M|mungo]]' wool in Batley, Yorkshire. This material combined recycled fibres with virgin [[wool]]. The [[West Yorkshire]] shoddy industry in towns such as Batley and Dewsbury, lasted from the early 19th century to at least 1914. |

||

| − | |||

| − | [[Image:salvage.jpg|thumb|Publicity photo for US [[aluminum]] salvage campaign in 1942]] |

||

| − | |||

| − | Industrialization spurred demand for affordable materials; aside from rags, ferrous scrap metals were coveted as they were cheaper to acquire than was virgin ore. Railroads both purchased and sold scrap metal in the 19th century, and the growing steel and automobile industries purchased scrap in the early 20th century. Many secondary goods were collected, processed, and sold by peddlers who combed dumps, city streets, and went door to door looking for discarded machinery, pots, pans, and other sources of metal. By [[World War I]], thousands of such peddlers roamed the streets of [[United States|American]] cities, taking advantage of market forces to recycle post-consumer materials back into industrial production.<ref name="cash">{{Cite book | last = Carl A. Zimring | publisher = Rutgers University Press | year = 2005 | location = New Brunswick, NJ | isbn = 081354694X | title = Cash for Your Trash: Scrap Recycling in America}}</ref> |

||

| + | In Pre-industrial times, there is evidence of scrap bronze and other metals being collected in Europe and melted down for perpetual reuse, |

||

| − | ===Wartime=== |

||

| − | Resource shortages caused by the [[world war]]s, and other such world-changing occurrences greatly encouraged recycling.<ref>''Out of the Garbage-Pail into the Fire: fuel bricks now added to the list of things salvaged by science from the nation's waste'', [[Popular Science]] monthly, February 1919, page 50-51, Scanned by Google Books: http://books.google.com/books?id=7igDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA50</ref> Massive government promotion campaigns were carried out in [[World War II]] in every country involved in the war, urging citizens to donate metals and conserve fibre, as a matter of significant patriotic importance. For example in 1939, Britain launched the programme [[Paper Salvage 1939-1950|Paper Salvage]] to encourage the recycling of materials to aid the war effort. Resource conservation programs established during the war were continued in some countries without an abundance of natural resources, such as [[Japan]], after the war ended. |

||

| + | [[Image:Picture_39.png|thumb|236px|Americans recycled just 6 percent in 1960 and 16 percent in 1990, but we recycle about 31 percent in 2006]] |

||

| − | ===Post-war=== |

||

| + | The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has also concluded in favor of recycling, saying that recycling efforts reduced the country's Carbon emissions by a net 49 Metric tonnes in 2005. John Tierney's extensive New York Times article, titled "Recycling is Garbage", was also highly critical of recycling, saying "the simplest and cheapest option is usually to bury garbage in an environmentally safe landfill", and claiming that "recycling may be the most wasteful activity in modern America: a waste of time and money, a waste of human and natural resources". |

||

| − | The next big investment in recycling occurred in the 1970s, due to rising energy costs. Recycling aluminium uses only 5% of the energy required by virgin production; glass, paper and metals have less dramatic but very significant energy savings when recycled feedstock is used.<ref name="economistrecycle"/> |

||

| − | ==Legislation== |

||

===Supply=== |

===Supply=== |

||

| + | In order for a recycling program to work, having a large, stable supply of recyclable material is crucial. Three legislative options have been used to create such a supply: mandatory recycling collection, Container deposit legislation, and refuse bans. Mandatory collection laws set recycling targets for cities to aim for, usually in the form that a certain percentage of a material must be diverted from the city's waste stream by a target date. The city is then responsible for working to meet this target. |

||

| + | Governments have used their own Purchasing power to increase recycling demand through what are called "procurement policies". These policies are either "set-asides", which earmark a certain amount of spending solely towards recycled products, or "price preference" programs which provide a larger budget when recycled items are purchased. Additional regulations can target specific cases: in the US, for example, the United States Environmental Protection Agency mandates the purchase of oil, paper, tires and building insulation from recycled or re-refined sources whenever possible. |

||

| − | For a recycling program to work, having a large, stable [[supply and demand|supply]] of recyclable material is crucial. Three legislative options have been used to create such a supply: mandatory recycling collection, [[container deposit legislation]], and refuse bans. Mandatory collection laws set recycling targets for cities to aim for, usually in the form that a certain percentage of a material must be diverted from the city's waste stream by a target date. The city is then responsible for working to meet this target.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | Lead-acid batteries, like those used in Automobiles, are relatively easy to recycle and many regions have legislation requiring vendors to accept used products. In the United States, the recycling rate is 90%, with new batteries containing up to 80% recycled material. Any grade of steel can be recycled to top quality new metal, with no 'downgrading' from prime to lower quality materials as steel is recycled repeatedly. 42% of crude steel produced is recycled material. |

||

| − | Container deposit legislation involves offering a refund for the return of certain containers, typically glass, plastic, and metal. When a product in such a container is purchased, a small surcharge is added to the price. This surcharge can be reclaimed by the consumer if the container is returned to a collection point. These programs have been very successful, often resulting in an 80 percent recycling rate. Despite such good results, the shift in collection costs from local government to industry and consumers has created strong opposition to the creation of such programs in some areas.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | ==Guide to Recycling== |

||

| − | A third method of increase supply of recyclates is to [[ban (law)|ban]] the disposal of certain materials as waste, often including used oil, old batteries, tires and garden waste. One aim of this method is to create a viable economy for proper disposal of banned products. Care must be taken that enough of these recycling [[service (economics)|services]] exist, or such bans simply lead to increased [[fly-tipping|illegal dumping]].<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | [[Image:Recyclingguide.png]] |

||

| − | ===Government-mandated demand=== |

||

| − | Legislation has also been used to increase and maintain a demand for recycled materials. Four methods of such legislation exist: minimum recycled content mandates, utilization rates, [[procurement]] policies, recycled [[Mandatory labeling|product labeling]].<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| − | Both minimum recycled content mandates and utilization rates increase demand directly by forcing manufacturers to include recycling in their operations. Content mandates specify that a certain percentage of a new product must consist of recycled material. Utilization rates are a more flexible option: industries are permitted to meet the recycling targets at any point of their operation or even contract recycling out in exchange for [trade]able credits. Opponents to both of these methods point to the large increase in reporting requirements they impose, and claim that they rob industry of necessary flexibility.<ref name="gar"/><ref name="DeLong">{{cite web |

||

| − | | url=http://jamesvdelong.com/articles/environmental/wasting-away.html |

||

| − | | title=Regulatory Policy Center - PROPERTY MATTERS - James V. DeLong |

||

| − | | accessdate=2008-02-28}}</ref> |

||

| + | ===[[Metal recycling]]=== |

||

| − | [[Governments]] have used their own [[purchasing power]] to increase recycling demand through what are called "procurement policies." These policies are either "set-asides," which earmark a certain amount of spending solely towards recycled products, or "price preference" programs which provide a larger [[government budget|budget]] when recycled items are purchased. Additional regulations can target specific cases: in the [[United States]], for example, the [[United States Environmental Protection Agency|Environmental Protection Agency]] mandates the purchase of oil, paper, tires and building insulation from recycled or re-refined sources whenever possible.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | [[Image:Recylablematerials.png|302px|things we recycle]] |

||

| + | Aluminum is shredded and ground into small pieces or crushed into bales. These pieces or bales are melted in an aluminum smelter to produce molten aluminum. By this stage the recycled aluminum is indistinguishable from virgin aluminum and further processing is identical for both. This process does not produce any change in the metal, so aluminum can be recycled indefinitely. |

||

| + | Recycling aluminum saves 95% of the energy cost of processing new aluminum. |

||

| − | The final government regulation towards increased demand is recycled product labeling. When producers are required to label their packaging with amount of recycled material in the product (including the packaging), consumers are better able to make educated choices. Consumers with sufficient [[buying power]] can then choose more environmentally conscious options, prompt producers to increase the amount of recycled material in their products, and indirectly increase demand. Standardized recycling labeling can also have a positive effect on supply of recyclates if the labeling includes information on how and where the product can be recycled.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | [[Image:West_recycles.jpg|250px|glass and aluminum recycling bin]] |

||

| − | ==Recycling [[consumer waste]]== |

||

| − | ===Collection=== |

||

| − | [[Image:DeutscheBahnRecycling20050814 CopyrightKaihsuTai Rotated.jpg|thumb|upright|Recycling and [[rubbish bin]] in a [[Germany|German]] [[railway station]].]] |

||

| + | ===Glass recycling=== |

||

| − | A number of different systems have been implemented to collect recyclates from the general waste stream. These systems lie along the spectrum of trade-off between public convenience and government ease and expense. The three main categories of collection are "drop-off centres", "buy-back centres" and "curbside collection".<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | Glass bottles and jars are gathered via curbside collection schemes and bottle banks, where the glass may be sorted into color categories. The collected glass c''ullet'' is taken to a glass recycling plant where it is monitored for purity and contaminants are removed. The cullet is crushed and added to a raw material mix in a melting furnace. It is then mechanically blown or molded into new jars or bottles. Glass cullet is also used in the construction industry for aggregate and glassphalt. Glass is a road-laying material which comprises around 30% recycled glass. Glass can be recycled indefinitely as its structure does not deteriorate when reprocessed. |

||

| − | ====Drop-off centres==== |

||

| − | Drop off centres require the waste producer to carry the recyclates to a central location, either an installed or mobile collection station or the reprocessing plant itself. They are the easiest type of collection to establish, but suffer from low and unpredictable throughput. |

||

| + | However, recycling glass costs more energy than producing new glass and its environmental friendliness have therefore been questioned. |

||

| − | ====Buy-back centres==== |

||

| − | Buy-back centres differ in that the cleaned recyclates are purchased, thus providing a clear incentive for use and creating a stable supply. The post-processed material can then be sold on, hopefully creating a profit. Unfortunately government subsidies are necessary to make buy-back centres a viable enterprise, as according to the United States Nation Solid Wastes Management Association it costs on average US$50 to process a ton of material, which can only be resold for US$30.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| − | === |

+ | ===[[Paper recycling]]=== |

| + | Paper can be recycled by reducing it to Pulp and combing it with pulp from newly harvested wood. As the recycling process causes the paper fibres to breakdown, each time paper is recycled its quality decreases. This means that either a higher percentage of new fiber must be added, or the paper downcycled into lower quality products. Any writing or colouration of the paper must first be removed by Deinking, which also removes fillers, clays, and fiber fragments. |

||

| − | {{Main|Curbside collection}} |

||

| − | Curbside collection encompasses many subtly different systems, which differ mostly on where in the process the recyclates are sorted and cleaned. The main categories are mixed waste collection, commingled recyclables and source separation.<ref name="gar"/> A [[waste collection vehicle]] generally picks up the waste. |

||

| + | Almost all paper can be recycled today, but some types are harder to recycle than others. Papers coated with plastic or aluminium foil, and papers that are waxed, pasted, or gummed are usually not recycled because the process is too expensive. Gift wrap paper also cannot be recycled due to the its already low quality. |

||

| − | [[Image:ACT recycling truck.jpg|thumb|A recycling truck collecting the contents of a recycling bin in [[Canberra, Australia]].]] |

||

| + | ===Import and export of recyclates=== |

||

| − | At one end of the spectrum is mixed waste collection, in which all recyclates are collected mixed in with the rest of the waste, and the desired material is then sorted out and cleaned at a central sorting facility. This results in a large amount of recyclable waste, paper especially, being too soiled to reprocess, but has advantages as well: the city need not pay for a separate collection of recyclates and no public education is needed. Any changes to which materials are recyclable is easy to accommodate as all sorting happens in a central location.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | The value of recyclates can be seen by the fact that certain countries have begun to import the unprocessed materials. Some have complained that the ultimate fate of recyclates sold to another country is unknown and they may end up in landfill instead of reprocessed. Pieter van Beukering, an economist specializing in waste imports of People's Republic of China and India, believes however that it is unlikely that bought materials would merely be dumped in landfill. Instead, he claims that the import of recyclables allows for large-scale reprocessing, improving both the fiscal and environmental return through Economies of scale. |

||

| − | In a Commingled or [[Single-stream recycling|single-stream system]], all recyclables for collection are mixed but kept separate from other waste. This greatly reduces the need for post-collection cleaning but does require [[public education]] on what materials are recyclable.<ref name="gar"/><ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| + | In some cases the cost of recycling is greater than the cost of putting garbage into a landfill. One example is the city of Santa Clarita, California which was paying $28 per ton to put garbage into a landfill. The city then adopted a diaper recycling program that cost $1,800 per ton. |

||

| − | Source separation is the other extreme, where each material is cleaned and sorted prior to collection. This method requires the least post-collection sorting and produces the purest recyclates, but incurs additional [[operating cost]]s for collection of each separate material. An extensive public education program is also required, which must be successful if recyclate contamination is to be avoided.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | All recycling techniques consume energy for transportation and processing and some also use considerable amounts of water, although recycling processes seldom amount to the level of resource use associated with raw materials processing. |

||

| − | Source separation used to be the preferred method due to the high sorting costs incurred by commingled collection. Advances in sorting technology (see [[Recycling#Sorting|sorting]] below), however, have lowered this overhead substantially—many areas which had developed source separation programs have since switched to comingled collection.<ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| + | There may also be drawbacks with the collection methods associated with recycling. Increasing collections of separated wastes adds to vehicle movements and the production of carbon dioxide. This may be negated however by centralized facilities such as some advanced Material and Mechanical biological treatment systems for the separation of mixed wastes. It has been calculated that collecting waste and disposing it in a landfill is about $60 a ton opposed to separate collecting and taking it to be recycled costs $150 a ton. |

||

| − | ===Sorting=== |

||

| − | [[Image:Glass and plastic recycling 065 ubt.JPG|thumb|right|Early sorting of recyclable materials: glass and plastic bottles in [[Poland]].]] |

||

| + | '''Styrofoam (Expanded Polystyrene)''' |

||

| − | Once commingled recyclates are collected and delivered to a [[Materials recovery facility|central collection facility]], the different types of materials must be sorted. This is done in a series of stages, many of which involve automated processes such that a truck-load of material can be fully sorted in less than an hour.<ref name="economisttruth"/> Some plants can now sort the materials automatically, known as [[single-stream recycling]]. A 30 percent increase in recycling rates has been seen in the areas where these plants exist.<ref>ScienceDaily. (2007). [http://www.sciencedaily.com/videos/2007/1002-recycling_without_sorting.htm Recycling Without Sorting Engineers Create Recycling Plant That Removes The Need To Sort].</ref> |

||

| + | Some recyclers prefer expanded polystyrene to be run through an [http://www.homeforfoam.com/city-governments/recycling-resources/recycling-equipment EPS Densifier], which melts the foam down to take up less room. Residential recyclers can use mealworms to digest and convert styrofoam into a biodegradable excretion. |

||

| − | Initially, the commingled recyclates are removed from the collection vehicle and placed on a conveyor belt spread out in a single layer. Large pieces of [[corrugated fiberboard]] and [[plastic bag]]s are removed by hand at this stage, as they can cause later machinery to jam.<ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| + | <strong>Wood Pallets and Dunnage</strong> |

||

| − | Next, automated machinery separates the recyclates by weight, splitting lighter paper and plastic from heavier glass and metal. Cardboard is removed from the mixed paper, and the most common types of plastic, [[Polyethylene terephthalate|PET]] (#1) and [[HDPE]] (#2), are collected. This separation is usually done by hand, but has become automated in some sorting centers: a [[Spectroscopy|spectroscopic]] scanner is used to differentiate between different types of paper and plastic based on the absorbed wavelengths, and subsequently divert each material into the proper collection channel.<ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| + | Vinyl dunnage bags were designed to be reusable. As long as there’s no contamination, the most cost-effective option is to put them back on the truck as many times as possible. Wood boards, planks and pallets can also be reused until they break. As long as they’re free from nails and staples, wood items can be ground up for mulch. The tricky part is finding a vendor that will take odd sized and damaged pallets and dunnage that is specific to your industry. |

||

| − | Strong magnets are used to separate out [[ferrous metal]]s, such as [[iron]], [[steel]], and [[Tin can|tin-plated steel cans]] ("tin cans"). [[Non-ferrous metals]] are ejected by [[magnetic eddy currents]] in which a rotating [[magnetic field]] [[electromagnetic induction|induces]] an electric current around the aluminium cans, which in turn creates a magnetic eddy current inside the cans. This magnetic eddy current is repulsed by a large magnetic field, and the cans are ejected from the rest of the recyclate stream.<ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| + | <strong>White Goods</strong> |

||

| − | Finally, glass must be sorted by hand based on its color: brown, amber, green or clear.<ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| + | Since the creation of the [https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-air-act Clean Air Act], companies and individuals must find an EPA compliant recycler to remove Freon and document its removal. Failure to follow the EPA guidelines and provide proper documentation can result in your company being slapped with a fine. But once you have the Freon removed, metal and other materials in these appliances can be recycled and rebates can be earned. If you’re recycling white goods in bulk, you may even be able to create a revenue stream. |

||

| − | ==Recycling [[Industrial waste]] == |

||

| − | Although many government programs are concentrated on recycling at home, a large portion of waste is generated by industry. The focus of many recycling programs done by industry is the cost-effectiveness of recycling. The ubiquitous nature of cardboard packaging makes cardboard a commonly recycled waste product by companies that deal heavily in packaged goods, like [[retail store]]s, [[warehouse]]s, and [[distributor]]s of goods. Other industries deal in niche or specialized products, depending on the nature of the waste materials that are present. |

||

| + | ===Other Techniques=== |

||

| − | The glass, lumber, [[wood pulp]], and paper manufacturers all deal directly in commonly recycled materials. However, old [[rubber tires]] may be collected and recycled by independent tire dealers for a profit. |

||

| + | Several other materials are also commonly recycled, frequently at an industrial level. |

||

| + | Ship breaking is one example that has associated environmental, health, and safety risks for the area where the operation takes place; balancing all these considerations is an Environmental justice problem. |

||

| − | Levels of metals recycling are generally low. In 2010, the [[International Resource Panel]], hosted by the [[United Nations Environment Programme]] (UNEP) published reports on metal stocks that exist within society<Ref> [http://www.unep.org/resourcepanel/Publications/tabid/54044/Default.aspx ''Metal Stocks in Society: Scientific Synthesis''] 2010, [[International Resource Panel]], [[United Nations Environment Programme]]</Ref> and their recycling rates.<Ref>[http://www.unep.org/resourcepanel/Publications/tabid/54044/Default.aspx ''The Recycling Rates of Metals: A Status Report''] 2010, [[International Resource Panel]], [[United Nations Environment Programme]]</Ref> The Panel reported that the increase in the use of metals during the 20th and into the 21st century has led to a substantial shift in metal stocks from below ground to use in applications within society above ground. For example, the in-use stock of copper in the USA grew from 73 to 238kg per capita between 1932 and 1999. |

||

| + | Tires are also commonly recycled. Used tires can be added to Asphalt for producing road surfaces or to make Rubber mulch used on playgrounds for safety. |

||

| − | The report authors observed that, as metals are inherently recyclable, the metals stocks in society can serve as huge mines above ground. However, they found that the recycling rates of many metals are very low. The report warned that the recycling rates of some rare metals used in applications such as mobile phones, battery packs for hybrid cars and fuel cells, are so low that unless future end-of-life recycling rates are dramatically stepped up these critical metals will become unavailable for use in modern technology. |

||

| + | ==Sustainable design== |

||

| − | The military recycles some metals. The [[U.S. Navy]]'s Ship Disposal Program uses [[ship breaking]] to reclaim the steel of old vessels. Ships may also be sunk to create an [[artificial reef]]. [[Uranium]] is a very dense metal that has qualities superior to lead and [[titanium]] for many military and industrial uses. The [[uranium]] left over from processing it into [[nuclear weapon]]s and fuel for [[nuclear reactor]]s is called [[depleted uranium]], and it is used by all branches of the U.S. military use for armour-piercing shells and shielding. |

||

| + | Much of the difficulty inherent in recycling comes from the fact that most products are not designed with recycling in mind. The concept of Sustainable design aims to solve this problem, and was first laid out in the book "''Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things''" by Architect William McDonough and Chemist Michael Braungart. They suggest that every product (and all packaging they require) should have a complete "closed-loop" cycle mapped out for each component—a way in which every component will either return to the natural ecosystem through Biodegradation or be recycled indefinitely. |

||

| − | The construction industry may recycle concrete and old road surface pavement, selling their waste materials for profit. |

||

| + | [[Image:bin.jpg|right|Fig. 1. Example of well-designed recycling bin ]] |

||

| − | ==Recycling codes== |

||

| − | In order to meet recyclers' needs while providing manufacturers a consistent, uniform system, a [[Recycling codes|coding system]] is developed. The recycling code for plastics was introduced in 1988 by plastics industry through the [[Society of the Plastics Industry|Society of the Plastics Industry, Inc]].<ref>[http://www.americanchemistry.com/s_plastics/bin.asp?CID=1102&DID=4645&DOC=FILE.PDF Plastic Recycling codes], American Chemistry</ref> Because municipal recycling programs traditionally have targeted packaging – primarily bottles and containers – the [[resin identification code|resin coding system]] offered a means of identifying the resin content of bottles and containers commonly found in the residential waste stream.<ref>[http://www.americanchemistry.com/s_plastics/doc.asp?cid=1102&did=4644 About resin identification codes] American Chemistry</ref> |

||

| + | Moreover, recycling bins are designed with various shapes and colors, which can also affect the recycling rate. Whereas some recycling bins are properly labeled and have specialized container lids, other recycling bins are poorly labeled and do not have specialized container lids. |

||

| − | ==[[Cost]]-benefit analysis== |

||

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; font-size:85%; margin-left:1em;" |

||

| − | |+ Environmental effects of recycling<ref>Unless otherwise indicated, this data is taken from {{cite book |

||

| − | | last = The League of Women Voters |

||

| − | | title = The Garbage Primer |

||

| − | | publisher = Lyons & Burford |

||

| − | | year = 1993 |

||

| − | | location = New York |

||

| − | | pages = 35–72 |

||

| − | | isbn = 1558218507}}, which attributes, "''Garbage Solutions: A Public Officials Guide to Recycling and Alternative Solid Waste Management Technologies,'' as cited in ''Energy Savings from Recycling,'' January/February 1989; and Worldwatch 76 ''Mining Urban Wastes: The Potential for Recycling,'' April 1987."</ref> |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | !Material |

||

| − | ![[Energy]] savings |

||

| − | ![[Air pollution]] savings |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | | [[Aluminium recycling|Aluminium]] || 95%<ref name="gar"/><ref name="economistrecycle"/> || 95%<ref name="gar"/><ref name='WasteOnline'>{{cite web |

||

| − | | title = Recycling metals - aluminium and steel |

||

| − | | url = http://www.wasteonline.org.uk/resources/InformationSheets/metals.htm |

||

| − | | accessdate = 2007-11-01}}</ref> |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | | [[Paper recycling|Cardboard]] || 24% || — |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | | [[Glass recycling|Glass]] || 5-30% || 20% |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | | [[Paper recycling|Paper]] || 40%<ref name="economistrecycle"/> || 73% |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | | [[Plastic recycling|Plastics]] || 70%<ref name="economistrecycle"/> || — |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | | [[Ferrous metal recycling|Steel]] || 60%<ref name="economisttruth"/> || — |

||

| − | |} |

||

| + | The recycling bin in Figure 1 is well-designed because it is clearly labeled and has a specialized lid that reduces the amount of trash entering the recycling stream. |

||

| − | There is some debate over whether recycling is [[economics|economically]] efficient. [[Municipality|Municipalities]] often see [[finance|fiscal]] benefits from implementing recycling programs, largely due to the reduced [[landfill]] costs.<ref>Lavee D. (2007). [http://www.springerlink.com/content/r461lju585760316/ Is Municipal Solid Waste Recycling Economically Efficient?] ''Environmental Management''.</ref> A study conducted by the [[Technical University of Denmark]] found that in 83 percent of cases, recycling is the most efficient method to dispose of household waste.<ref name="economisttruth">{{cite news | title = The truth about recycling | date = June 7, 2007 | url = http://www.economist.com/opinion/displaystory.cfm?story_id=9249262 | publisher = The Economist}}</ref><ref name="economistrecycle">{{cite news | title = The price of virtue | date = June 7, 2007 | url = http://www.economist.com/opinion/displaystory.cfm?story_id=9302727 | publisher = The Economist}}</ref> However, a 2004 assessment by the Danish Environmental Assessment Institute concluded that incineration was the most effective method for disposing of drink containers, even aluminium ones.<ref name=Vigso2004>{{cite journal | last = Vigso | first = Dorte | year = 2004 | title = Deposits on single use containers - a social cost-benefit analysis of the Danish deposit system for single use drink containers | journal = Waste Management & Research | volume = 22 | issue = 6 | page = 477 | doi = 10.1177/0734242X04049252 | url = http://wmr.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/22/6/477 | pmid = 15666450}}</ref> |

||

| + | [[Image:bin2.jpg|thumb|right| Fig. 2. Example of poorly designed recycling bin]] |

||

| − | Fiscal efficiency is separate from economic efficiency. Economic analysis of recycling includes what economists call [[externality|externalities]], which are unpriced costs and benefits that accrue to individuals outside of private transactions. Examples include: decreased air pollution and greenhouse gases from incineration, reduced hazardous waste leaching from landfills, reduced [[energy (society)|energy]] consumption, and reduced [[waste]] and [[resource]] consumption, which leads to a reduction in environmentally damaging [[mining]] and [[timber]] activity. About 4000 [[mineral]]s are known, of these only a few hundred minerals in the world are relatively common.<ref>"[http://faculty.uml.edu/Nelson_Eby/89.215/Assignments/Mineral%20Identification.pdf Minerals and Forensic Science]" (PDF). [[University of Massachusetts Lowell]], Department of Environmental, Earth, & Atmospheric Sciences.</ref> At current rates, current known reserves of [[phosphorus]] will be depleted in the next 50 to 100 years.<ref>"[http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=phosphorus-a-looming-crisis Phosphorus Famine: The Threat to Our Food Supply]". ''Scientific American''. June 2009</ref><ref>"[http://reason.com/archives/2010/04/27/peak-everything Peak Everything?]". [[Reason Magazine]]. April 27, 2010.</ref> Without mechanisms such as taxes or subsidies to internalize externalities, businesses will ignore them despite the costs imposed on society. To make such non-fiscal benefits economically relevant, advocates have pushed for [[law|legislative]] action to increase the [[demand]] for recycled materials.<ref name="gar"/> The [[United States Environmental Protection Agency]] (EPA) has concluded in favor of recycling, saying that recycling efforts reduced the country's [[carbon emissions]] by a net 49 million [[metric tonnes]] in 2005.<ref name="economisttruth"/> In the United Kingdom, the [[Waste and Resources Action Programme]] stated that Great Britain's recycling efforts reduce [[Greenhouse gas|CO<sub>2</sub> emissions]] by 10-15 million tonnes a year.<ref name="economisttruth"/> Recycling is more efficient in densely populated areas, as there are [[economies of scale]] involved.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | The recycling bin in Figure 2, however, is poorly designed because it is not clearly labeled. And despite its novel appearance, it is not clear whether this bin is used for recycling bottles or for marketing sodas. Given this ambiguity, a person may be more likely to dispose of their used bottle in the trash bin, which directly located in front of that recycling bin. |

||

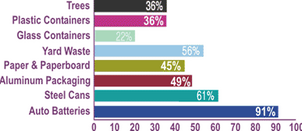

| + | These variations in design can dramatically affect whether a person deposits their recyclables into a recycling bin or trashcan. In a recent study, the number of bottles discarded into 30 waste bins was counted during a four-week period. To determine whether using specialized lids affected the recycling rate, 15 bins had specialized lids and 15 bins did not have specialized lids (see Figure 3 below). |

||

| − | Certain requirements must be met for recycling to be economically feasible and environmentally effective. These include an adequate source of recyclates, a system to extract those recyclates from the [[waste stream]], a nearby [[factory]] capable of reprocessing the recyclates, and a potential demand for the recycled products. These last two requirements are often overlooked—without both an industrial [[market]] for production using the collected materials and a consumer market for the manufactured goods, recycling is incomplete and in fact only "collection".<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | [[Image:bins.jpg|center|Fig. 3. Bins with (and without) specialized lids]] |

||

| − | Many economists favor a moderate level of government intervention to provide recycling services. Economists of this mindset probably view product disposal as an externality of production and subsequently argue government is most capable of alleviating such a dilemma. However, those of the [[laissez faire]] approach to municipal recycling see product disposal as a service that consumers value. A free-market approach is more likely to suit the preferences of consumers since profit-seeking businesses have greater incentive to produce a quality product or service than does government. Moreover, economists almost always advise against government intrusion in any market with little or no externalities.<ref>Gunter, Matthew. "Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Household and Municipal Recycling?" (January 2007). [http://econjwatch.org/issues/volume-4-number-1-january-2007]</ref> |

||

| + | Results showed significant differences in the amount of recyclables disposed into recycling bins or trashcans. These differences were based on whether specialized lids were on or off the bins. When specialized lids were used, the recycling rate was 92%, and only 8% of recyclables were thrown into trashcans. However, when specialized lids were not used, the recycling rate was 57%, and 43% of recyclables were thrown into trashcans. |

||

| − | ===Trade in recyclates=== |

||

| − | [[Image:Computer Recycling.JPG|thumb|Computers being collected for recycling at a pick up event in [[Olympia, Washington]], United States.]] |

||

| + | [[Image:Recyclebindata.jpg|400px|center|Fig.4. Results from recycle-bin experiment]] |

||

| − | Certain countries trade in unprocessed recyclates. Some have complained that the ultimate fate of recyclates sold to another country is unknown and they may end up in landfills instead of reprocessed. According to one report, in America, 50–80 percent of computers destined for recycling are actually not recycled.<ref>[http://www.usatoday.com/tech/news/2002/02/25/computer-waste.htm Much toxic computer waste lands in Third World]</ref><ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20031109231707/http://svtc.igc.org/media/articles/2002/time_march.htm Environmental and health damage in China]</ref> There are reports of illegal-waste imports to China being dismantled and recycled solely for monetary gain, without consideration for workers' health or environmental damage. Though the Chinese government has banned these practices, it has not been able to eradicate them.<ref>[http://www.cbc.ca/mrl3/23745/thenational/archive/ewaste-102208.wmv Illegal dumping and damage to health and environment]</ref> In 2008, the prices of recyclable waste plummeted before rebounding in 2009. Cardboard averaged about £53/tonne from 2004–2008, dropped to £19/tonne, and then went up to £59/tonne in May 2009. PET plastic averaged about £156/tonne, dropped to £75/tonne and then moved up to £195/tonne in May 2009.<ref>Hogg M. [http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/feebdb2a-419d-11de-bdb7-00144feabdc0.html Waste outshines gold as prices surge]. ''Financial Times''.{{Registration required}}</ref> |

||

| + | These findings reveal the importance of using sustainable designs for waste bins. Notice how the recycling rate increased by 34% when specialized lids were used. In addition, the amount of recyclables entering landfills decreased by 35%. These changes occurred despite the fact that all bins were correctly labeled at all times. In sum, recycling bins designed with the principles of sustainability offset the number recyclables entering the general waste stream, thus diverting valuable resources that may be reused and recycled back into the consumer market. |

||

| − | Certain regions have difficulty using or exporting as much of a material as they recycle. This problem is most prevalent with glass: both Britain and the U.S. import large quantities of wine bottled in green glass. Though much of this glass is sent to be recycled, outside the [[American Midwest]] there is not enough wine production to use all of the reprocessed material. The extra must be downcycled into building materials or re-inserted into the regular waste stream.<ref name="gar"/><ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| + | == Related wiki == |

||

| − | Similarly, the [[northwestern United States]] has difficulty finding markets for recycled newspaper, given the large number of [[pulp mill]]s in the region as well as the proximity to Asian markets. In other areas of the U.S., however, demand for used newsprint has seen wide fluctuation.<ref name="gar"/> |

||

| + | * [[w:c:sca21|Sustainable Community Action]] - [[w:c:sca21:Reduce, reuse, repair & recycle|Reduce, reuse, repair & recycle]] |

||

| − | |||

| − | In some U.S. states, a program called [[RecycleBank]] pays people with coupons to recycle, receiving money from local municipalities for the reduction in landfill space which must be purchased. It uses a single stream process in which all material is automatically sorted.<ref>Bonnie DeSimone. (2006). [http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/21/business/businessspecial2/21recycle.html?_r=2&oref=slogin&oref=slogin Rewarding Recyclers, and Finding Gold in the Garbage]. ''New York Times''.</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | ==Benefits and Criticisms== |

||

| − | Much of the difficulty inherent in recycling comes from the fact that most products are not designed with recycling in mind.{{Citation needed|date=August 2010}} The concept of [[sustainable design]] aims to solve this problem, and was laid out in the book "''[[Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things]]''" by [[architect]] William McDonough and [[chemist]] Michael Braungart. They suggest that every product (and all packaging they require) should have a complete "closed-loop" cycle mapped out for each component—a way in which every component will either return to the natural ecosystem through [[biodegradation]] or be recycled indefinitely.<ref name="economisttruth"/> |

||

| − | |||

| − | As with environmental economics, care must be taken to ensure a complete view of the costs and benefits involved. For example, cardboard packaging for food products is more easily recycled than plastic, but is heavier to ship and may result in more waste from spoilage.<ref name="Tierney">{{cite news |

||

| − | | first = John |

||

| − | | last = Tierney |

||

| − | | title = Recycling Is Garbage |

||

| − | | url = http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=990CE1DF1339F933A05755C0A960958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1 |

||

| − | | publisher = New York Times |

||

| − | | location = New York |

||

| − | | page = 3 |

||

| − | | date = June 30, 1996 |

||

| − | | accessdate = 2008-02-28}}</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | The following are criticisms of many popular points used for recycling. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Saves [[energy]]=== |

||

| − | The amount of [[energy]] saved through recycling depends upon the material being recycled. Some, such as aluminum, save a great deal, while others may not save any. The [[Energy Information Administration]] (EIA) states on its website that "a paper mill uses 40 percent less energy to make paper from recycled paper than it does to make paper from fresh lumber."<ref>Energy Information Administration [http://www.eia.doe.gov/kids/energyfacts/saving/recycling/solidwaste/paperandglass.html#SavingEnergy Recycling Paper & Glass]. Retrieved 18 October 2006.</ref> Some critics argue that it takes more energy to produce recycled products than it does to dispose of them in traditional [[landfill]] methods, since the [[Kerbside collection|curbside collection]] of [[recyclable waste|recyclables]] often requires a second [[waste collection vehicle|waste truck]]. However, recycling proponents point out that a second timber or logging truck is eliminated when paper is collected for recycling, so the net energy consumption is the same. |

||

| − | |||

| − | It is difficult to determine the exact amount of energy consumed or produced in waste disposal processes. How much energy is used in recycling depends largely on the type of material being recycled and the process used to do so. [[Aluminium]] is generally agreed to use far less energy when recycled rather than being produced from scratch. The EPA states that "recycling aluminum cans, for example, saves 95 percent of the energy required to make the same amount of aluminum from its virgin source, [[bauxite]]."<ref>Environmental Protection Agency [http://www.epa.gov/msw/faq.htm#5 Frequently Asked Questions about Recycling and Waste Management]. Retrieved 18 October 2006.</ref><ref>[http://www1.eere.energy.gov/industry/aluminum/pdfs/aluminum.pdf Energetics, Inc. Et. all (1997). "Energy and Environmental Profile of the U.S. Aluminum Industry" Page 5,6.]</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | Economist Steven Landsburg has suggested that the sole benefit of reducing landfill space is trumped by the energy needed and resulting pollution from the recycling process.<ref name="landsburg">Landsburg, Steven A. ''The Armchair Economist.'' p. 86.</ref> Others, however, have calculated through [[life cycle assessment]] that producing recycled paper uses less [[energy]] and [[water]] than harvesting, pulping, processing, and transporting virgin trees.<ref>Selke 116</ref> When less recycled paper is used, additional energy is needed to create and maintain farmed [[forests]] until these forests are as self-sustainable as virgin [[forests]]. |

||

| − | |||

| − | Other studies have shown that recycling in itself is inefficient to perform the “decoupling” of economic development from the depletion of non-renewable raw materials that is necessary for sustainable development.<ref>[http://sapiens.revues.org/index906.html Grosse, F. (2010) “Is recycling 'part of the solution'? The role of recycling in an expanding society and a world of finite resources”. ''S.A.P.I.EN.S.'' '''3''' (1) ]</ref> When global consumption of a natural resource grows by more than 1 percent per annum, its depletion is inevitable {{Citation needed|date=March 2011}}, and the best recycling can do is to delay it by a number of years. Nevertheless, if this decoupling can be achieved by other means, so that consumption of the resource is reduced below 1 percent per annum, then recycling becomes indispensable – indeed recycling rates above 80 percent are required for a significant slowdown of the resource depletion. |

||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ===Saves [[money]]=== |

||

| − | [[Image:Man rummaging thought a skip.jpg|thumb|A man rummaging through a [[Skip (container)|skip]] at the back of an [[office]] building in [[Central London]] in 2006. The [[wood]] could be used for [[urban lumberjacking]] and the cardboard could be recycled.]] |

||

| − | |||

| − | The amount of money actually saved through recycling depends on the efficiency of the recycling program used to do it. The [[Institute for Local Self-Reliance]] argues that the cost of recycling depends on various factors around a community that recycles, such as [[gate fee|landfill fee]]s and the amount of disposal that the community recycles. It states that communities start to save money when they treat recycling as a replacement for their traditional waste system rather than an add-on to it and by "redesigning their collection schedules and/or trucks."<ref>Waste to Wealth [http://www.ilsr.org/recycling/wrrs/fivemyths.html The Five Most Dangerous Myths About Recycling]. Retrieved October 18, 2006.</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | In some cases, the [[cost]] of recyclable materials also exceeds the cost of raw materials. Virgin plastic resin costs 40 percent less than recycled resin.<ref>United States Department of Energy [http://www.eia.doe.gov/kids/energyfacts/saving/recycling/solidwaste/plastics.html Conserving Energy - Recycling Plastics]. Retrieved 10 November 2006.</ref> Additionally, a [[United States Environmental Protection Agency]] (EPA) study that tracked the price of clear [[glass]] from July 15 to August 2, 1991, found that the average cost per ton ranged from $40 to $60,<ref>Environmental Protection Agency [http://www.epa.gov/msw/pubs/cok.pdf Markets for Recovered Glass]. Retrieved 10 November 2006.</ref> while a [[USGS]] report shows that the cost per ton of raw silica sand from years 1993 to 1997 fell between $17.33 and $18.10.<ref>United States Geological Survey [http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/silica/780398.pdf Mineral Commodity Summaries]. Retrieved 10 November 2006.</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | In a 1996 article for ''[[The New York Times]]'', [[John Tierney (journalist)|John Tierney]] argued that it costs more money to recycle the trash of New York City than it does to dispose of it in a landfill. Tierney argued that the recycling process employs people to do the additional waste disposal, sorting, inspecting, and many fees are often charged because the processing costs used to make the end product are often more than the profit from its sale.<ref>[http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=98638760 Recycling Suddenly Gets Expensive : NPR<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Tierney also referenced a study conducted by the [[Solid Waste Association of North America]] (SWANA) that found in the six communities involved in the study, "all but one of the curbside recycling programs, and all the composting operations and [[waste-to-energy]] [[incinerator]]s, increased the cost of waste disposal."<ref name="A">New York Times [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=990CE1DF1339F933A05755C0A960958260&sec=&spon=&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink Recycling... Is Garbage (nytimes.com Published 30 June 1996)] [http://www.williams.edu/HistSci/curriculum/101/garbage.html Recycling... Is Garbage (article reproduced)] [http://www.heartland.org/Article.cfm?artId=4037 Recycling... Is Garbage (article reproduced)]. Retrieved 18 October 2006.</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | Tierney also points out that "the prices paid for scrap materials are a measure of their environmental value as recyclables. Scrap aluminum fetches a high price because recycling it consumes so much less energy than manufacturing new aluminum." |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Working conditions=== |

||

| − | |||

| − | The recycling of waste electrical and electronic equipment in India and China generates a significant amount of pollution. Informal recycling in an underground economy of these countries has generated an environmental and health disaster. High levels of lead (Pb), polybrominated diphenylethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated dioxins and furans as well as polybrominated dioxins and furans (PCDD/Fs and PBDD/Fs) concentrated in the air, bottom ash, dust, soil, water and sediments in areas surrounding recycling sites.<ref name="Sepúlveda10">{{cite journal | last1=Sepúlveda | first1=A. | last2=Schluep | first2=M. | last3=Renaud | first3=F. G. | last4=Streicher | first4=M. | last5=Kuehr | first5=R. | last6=Hagelüken | first6=C. | last7=et al. | title=A review of the environmental fate and effects of hazardous substances released from electrical and electronic equipments during recycling: Examples from China and India | journal=Environmental Impact Assessment Review | volume=30 | year=2010 | pages=28–41 | url=http://ewasteguide.info/files/Sepulveda_2010_EIAR_0_0.pdf | doi=10.1016/j.eiar.2009.04.001}}</ref> Critics also argue that while recycling may create jobs, they are often jobs with low wages and terrible working conditions.<ref>Heartland Institute [http://www.heartland.org/Article.cfm?artId=402 Recycling: It's a bad idea in New York]. Retrieved 18 October 2006.</ref> |

||

| − | These jobs are sometimes considered to be [[make-work job]]s that don't produce as much as the cost of wages to pay for those jobs. |

||

| − | In areas without many environmental regulations and/or worker protections, jobs involved in recycling such as [[ship breaking]] can result in deplorable conditions for both workers and the surrounding communities |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Saves [[trees]]=== |

||

| − | [[Image:Recycletree.jpg|right|thumb|[[Christmas trees]] gathered for recycling.]] |

||

| − | |||

| − | [[Economist]] [[Steven Landsburg]], author of a paper entitled "Why I Am Not an Environmentalist," <ref>http://www.shrubwalkers.com/prose/list/not.html</ref> has claimed that [[paper recycling]] actually reduces tree populations. He argues that because paper companies have incentives to replenish the [[forest]]s they own, large demands for paper lead to large forests. Conversely, reduced demand for paper leads to fewer "farmed" [[forests]].<ref name=autogenerated1>Landsburg, Steven A. ''The Armchair Economist.'' p. 81.</ref> Similar arguments were expressed in a 1995 article for The Free Market.<ref name="FM">The Free Market [http://www.mises.org/freemarket_detail.aspx?control=212 Don't Recycle: Throw It Away!]. Retrieved 4 November 2006.</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | <!-- if you have a problem with the valid sourced statements below, note your specific grievances in the talk page do not just remove them --> |

||

| − | |||

| − | When foresting companies cut down trees, more are planted in their place. Most paper comes from pulp [[forest]]s grown specifically for paper production.<ref name="A"/><ref name="FM"/><ref name="RPC">Regulatory Policy Center [http://jamesvdelong.com/articles/environmental/wasting-away.html WASTING AWAY: Mismanaging Municipal Solid Waste]. Retrieved November 4, 2006.</ref><ref name="JWR">Jewish World Review [http://www.jewishworldreview.com/cols/hart110599.asp The waste of recycling]. Retrieved 4 November 2006.</ref> Many [[environmentalist]]s point out, however, that "farmed" forests are inferior to virgin forests in several ways. Farmed forests are not able to fix the soil as quickly as virgin forests, causing widespread [[soil erosion]] and often requiring large amounts of [[fertilizer]] to maintain while containing little tree and wild-life [[biodiversity]] compared to virgin forests.<ref name="baird">Baird, Colin (2004) ''Environmental Chemistry'' (3rd ed.) W. H. Freeman ISBN 0-7167-4877-0</ref> Also, the new trees planted are not as big as the trees that were cut down, and the argument that there will be "more trees" is not compelling to [[forestry]] advocates when they are counting saplings. |

||

| − | |||

| − | The recycling of paper should not be confused with saving the tropical [[forest]]. Many people have the misconception that paper-making is what's causing [[deforestation]] of tropical [[rain forest]]s but rarely any tropical wood is harvested for paper. Deforestation is mainly caused by population pressure such as demand of more land for agriculture or construction use. Therefore, the recycling paper, although reduces demand of trees, doesn't greatly benefit the tropical [[rain forests]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tappi.org/paperu/all_about_paper/faq.htm|title=All About Paper |publisher=[[Paper University]]|accessdate=2009-02-12}}</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Possible income loss and social [[costs]]=== |

||

| − | In some prosperous and many less prosperous countries in the world, the traditional job of recycling is performed by the entrepreneurial poor such as the [[karung guni]], [[Zabaleen]], the [[rag and bone man]], [[waste picker]], and [[junk man]]. With the creation of large recycling organizations that may be profitable, either by law or [[economies of scale]],<ref>[http://www.nrdc.org/cities/recycling/recyc/appenda.asp NRDC: Too Good To Throw Away - Appendix A<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://www.sfgov.org/site/uploadedfiles/police/stations/ParkStation/2007/07feb08%20park%20newsletter.pdf Mission Police Station<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> the poor are more likely to be driven out of the recycling and the [[remanufacturing]] market. To compensate for this loss of income to the poor, a society may need to create additional forms of societal programs to help support the poor.<ref name="PBS NewsHour 2010">PBS NewsHour, February 16, 2010. Report on the Zabaleen</ref> Like the [[parable of the broken window]], there is a net loss to the poor and possibly the whole of a society to make recycling artificially profitable through law. However, as seen in Brazil and Argentina, waste pickers/informal recyclers are able to work alongside governments, in (semi)funded cooperatives, allowing informal recycling to be legitimized as a paying government job.<ref name="Medina, M. 2000 51–69">{{cite journal|author= Medina, M.|year=2000|title=Scavenger cooperatives in Asia and Latin America.|journal=Resources|volume=31|pages=51–69}}</ref> |

||

| − | |||

| − | Because the social support of a country is likely less than the loss of income to the poor doing recycling, there is a greater chance that the poor will come in conflict with the large recycling organizations.<ref>[http://www.zwire.com/site/news.cfm?newsid=16878461&BRD=1698&PAG=461&dept_id=21849&rfi=6 The News-Herald - Scrap metal a steal<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=92705125 Raids On Recycling Bins Costly To Bay Area : NPR<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> This means fewer people can decide if certain waste is more economically reusable in its current form rather than being reprocessed. Contrasted to the recycling poor, the efficiency of their recycling may actually be higher for some materials because individuals have greater control over what is considered “waste.”<ref name="PBS NewsHour 2010"/> |

||

| − | |||

| − | One labor-intensive underused waste is electronic and computer waste. Because this waste may still be functional and wanted mostly by the poor, the poor may sell or use it at a greater efficiency than large recyclers. |

||

| − | |||

| − | Many recycling advocates believe that this [[laissez-faire]] individual-based recycling does not cover all of society’s recycling needs. Thus, it does not negate the need for an organized recycling program.<ref name="PBS NewsHour 2010"/> Local government often consider the activities of the recycling poor as contributing to property blight. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Public participation in recycling programmes=== |

||

| − | |||

| − | Many studies have addressed recycling behaviour and strategies to encourage community involvement in recycling programmes. It has been argued <ref>[Schackelford, T.K. (2006) “Recycling, evolution and the structure of human personality”. ''Personality and Individual Differences'' '''41''' 1551-1556 ]</ref> that recycling behaviour is not natural because it requires a focus and appreciation for long term planning, whereas humans have evolved to be sensitive to short term survival goals; and that to overcome this innate predisposition, the best solution would be to use social pressure to compel participation in recycling programmes. However, recent studies have concluded that social pressure is unviable in this context.<ref>[http://sapiens.revues.org/index905.html Pratarelli, M.E. (2010) “Social pressure and recycling: a brief review, commentary and extensions”. ''S.A.P.I.EN.S.'' '''3''' (1) ]</ref> One reason for this is that social pressure functions well in small group sizes of 50 to 150 indiviudals (common to nomadic hunter-gatherer peoples) but not in communities numbering in the millions, as we see today. Another reason is that individual recycling does not take place in the public view. |

||

| − | In a study done by social psychologist Shawn Burn,<ref>Burn, Shawn. "Social Psychology and the Stimulation of Recycling Behaviors: The Block Leader Approach." Journal of Applied Social Psychology 21.8 (2006): 611-629.</ref> it was found that personal contact with individuals within a neighborhood is the most effective way to increase recycling within a community. In his study, he had 10 block leaders talk to their neighbors and convince them to recycle. A comparison group was sent fliers promoting recycling. It was found that the neighbors that were personally contacted by their block leaders recycled much more than the group without personal contact. As a result of this study, Shawn Burn believes that personal contact within a small group of people is an important factor in encouraging recycling. Another study done by Stuart Oskamp <ref>Oskamp, Stuart. "Resource Conservation and Recycling: Behavior and Policy." Journal of Social Issues 51.4 (1995): 157-177. Print.</ref> examines the effect of neighbors and friends on recycling. It was found in his studies that people who had friends and neighbors that recycled were much more likely to also recycle than those who didn’t have friends and neighbors that recycled. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ==See also== |

||

| − | *[[Index of recycling topics]] |

||

| − | *[[E-Cycling]] (recycling of electronic components) |

||

| − | *[[Plastic recycling]] |

||

| − | *[[Recycling bin]] |

||

| − | *[[Sustainability]] |

||

| − | *[[Recycling (ecological)]] |

||

| − | *[[2000s commodities boom]] |

||

| − | *[[Paint recycling]] |

||

| − | *[[Compost]] |

||

| − | *[[Treecycling]] |

||

| − | *[[Grasscycling]] |

||

| − | |||

| − | {{-}} |

||

| − | |||

| − | ==References== |

||

| − | {{Reflist|2}} |

||

| − | |||

| − | ==Further reading== |

||

| − | * Tierney, John. (1996). ''Recycling Is Garbage''. [[The New York Times]]. |

||

| − | * Ackerman, Frank. (1997). ''Why Do We Recycle?: Markets, Values, and Public Policy''. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-504-5, 9781559635042 |

||

| − | * Porter, Richard C. (2002). ''The economics of waste''. [[Resources for the Future]]. ISBN 1-891853-42-2, 9781891853425 |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

| + | *[http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/s_384807.html Pittsburgh tribune article criticizing curbside recycling] |

||

| − | *{{dmoz|Business/Environment/Waste_Management/Recycling/}} |

||

| + | *[https://www.wastedisposalsolutions.com/node/29 Waste Disposal Solutions Tough Materials to Recycle] |

||

| − | *{{cite web|url=http://www.recyclingwasteworld.co.uk/cgi-bin/go.pl/article/article.html?uid=47956|title=Study debunks myths around co-mingling|date=10 May 2010|publisher=Recycling Waste World}} |

||

| + | *[http://www.epa.gov/msw/recycle.htm EPA municipal solid waste-recycling] |

||

| − | *[http://www.clearitgreen.co.uk Recycling Office Waste] , Richard t Jones, CIWM, WAMITAB, Oct 2011 |

||

| + | *[http://mypage.iusb.edu/~mverges/Duffy&Verges_inpress.pdf Duffy, S., & Verges, M. (in press). Perceptual Affordances of Waste Containers Influence Recycling Compliance.''Environment and Behavior.''] |

||

| − | |||

| − | ==Video== |

||

| − | |||

| − | <videogallery> |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_1 |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_2_The_MRF |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_3_Paper |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_4_Metals |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_5_Plastic |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_6_Glass |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_7_Overseas |

||

| − | Video:The_Cycle_Chapter_8_RecycleBank |

||

| − | </videogallery> |

||

| − | {{Recycling}} |

||

| − | {{Waste}} |

||

| − | {{re}} |

||

| − | {{Climate control}} |

||

| − | {{Water conservation}} |

||

| − | {{Waste management}} |

||

| − | {{Habitat Conservation}} |

||

| − | [[Category:Waste management]] |

||

[[Category:Recycling]] |

[[Category:Recycling]] |

||

[[Category:Sustainable living]] |

[[Category:Sustainable living]] |

||

[[Category:Reduce Reuse and Recycle]] |

[[Category:Reduce Reuse and Recycle]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Water conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Forestry ]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Air Pollution]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Renewable energy]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Habitat Conservation ]] |

||

| − | [[Category:climate control]] |

||

| − | [[Category:oil conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Carbon dioxide conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Energy conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Mercury conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Landfill space conservation ]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Coal conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Greenhouse gas conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Limestone conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Gasoline conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Lead conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Money conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Chemical conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Fossil fuel conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:hydrogen conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Natural gas conservation]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Biomass conservation]] |

||

Latest revision as of 17:34, 12 December 2017

Recycling is the reprocessing of old materials into new products, with the aims of preventing the waste of potentially useful materials, reducing the consumption of fresh raw materials, reducing Energy consumed in conventional waste disposal. The overall result is a lowering of Greenhouse gases.

These materials are either brought to a collection center or picked-up from the curbside; and sorted , cleaned and reprocessed into new products bound for manufacturing.

To judge the environmental benefits of recycling, the cost of this entire process must be compared to the cost of virgin extraction. In order for recycling to be economically viable, there usually must be a steady supply of recyclates and constant demand for the reprocessed goods; both of which can be stimulated through government Legislation.

History

Recycling has been a common practice for most of human history, with recorded advocates as far back as Plato in 400 BC. During periods when resources were scarce, archaeological studies of ancient waste dumps show less household waste (such as ash, broken tools and pottery)—implying more waste was being recycled in the absence of new material.

In Pre-industrial times, there is evidence of scrap bronze and other metals being collected in Europe and melted down for perpetual reuse,

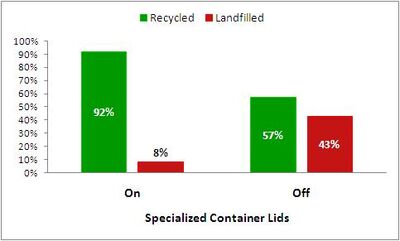

Americans recycled just 6 percent in 1960 and 16 percent in 1990, but we recycle about 31 percent in 2006

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has also concluded in favor of recycling, saying that recycling efforts reduced the country's Carbon emissions by a net 49 Metric tonnes in 2005. John Tierney's extensive New York Times article, titled "Recycling is Garbage", was also highly critical of recycling, saying "the simplest and cheapest option is usually to bury garbage in an environmentally safe landfill", and claiming that "recycling may be the most wasteful activity in modern America: a waste of time and money, a waste of human and natural resources".

Supply

In order for a recycling program to work, having a large, stable supply of recyclable material is crucial. Three legislative options have been used to create such a supply: mandatory recycling collection, Container deposit legislation, and refuse bans. Mandatory collection laws set recycling targets for cities to aim for, usually in the form that a certain percentage of a material must be diverted from the city's waste stream by a target date. The city is then responsible for working to meet this target.

Governments have used their own Purchasing power to increase recycling demand through what are called "procurement policies". These policies are either "set-asides", which earmark a certain amount of spending solely towards recycled products, or "price preference" programs which provide a larger budget when recycled items are purchased. Additional regulations can target specific cases: in the US, for example, the United States Environmental Protection Agency mandates the purchase of oil, paper, tires and building insulation from recycled or re-refined sources whenever possible.

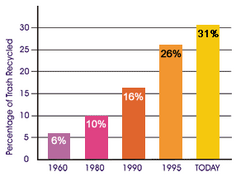

Lead-acid batteries, like those used in Automobiles, are relatively easy to recycle and many regions have legislation requiring vendors to accept used products. In the United States, the recycling rate is 90%, with new batteries containing up to 80% recycled material. Any grade of steel can be recycled to top quality new metal, with no 'downgrading' from prime to lower quality materials as steel is recycled repeatedly. 42% of crude steel produced is recycled material.

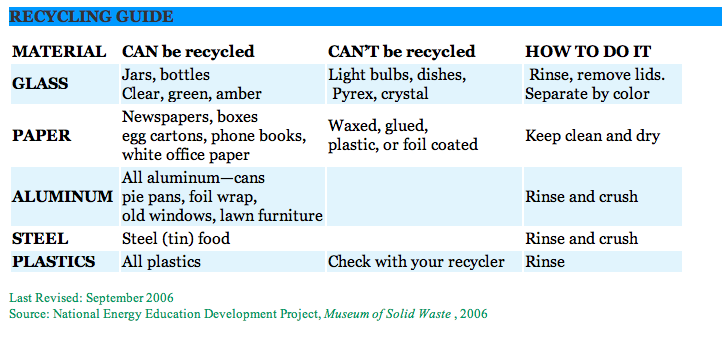

Guide to Recycling

Metal recycling

Aluminum is shredded and ground into small pieces or crushed into bales. These pieces or bales are melted in an aluminum smelter to produce molten aluminum. By this stage the recycled aluminum is indistinguishable from virgin aluminum and further processing is identical for both. This process does not produce any change in the metal, so aluminum can be recycled indefinitely.

Aluminum is shredded and ground into small pieces or crushed into bales. These pieces or bales are melted in an aluminum smelter to produce molten aluminum. By this stage the recycled aluminum is indistinguishable from virgin aluminum and further processing is identical for both. This process does not produce any change in the metal, so aluminum can be recycled indefinitely.

Recycling aluminum saves 95% of the energy cost of processing new aluminum.

Glass recycling

Glass bottles and jars are gathered via curbside collection schemes and bottle banks, where the glass may be sorted into color categories. The collected glass cullet is taken to a glass recycling plant where it is monitored for purity and contaminants are removed. The cullet is crushed and added to a raw material mix in a melting furnace. It is then mechanically blown or molded into new jars or bottles. Glass cullet is also used in the construction industry for aggregate and glassphalt. Glass is a road-laying material which comprises around 30% recycled glass. Glass can be recycled indefinitely as its structure does not deteriorate when reprocessed.

However, recycling glass costs more energy than producing new glass and its environmental friendliness have therefore been questioned.

Paper recycling

Paper can be recycled by reducing it to Pulp and combing it with pulp from newly harvested wood. As the recycling process causes the paper fibres to breakdown, each time paper is recycled its quality decreases. This means that either a higher percentage of new fiber must be added, or the paper downcycled into lower quality products. Any writing or colouration of the paper must first be removed by Deinking, which also removes fillers, clays, and fiber fragments.

Almost all paper can be recycled today, but some types are harder to recycle than others. Papers coated with plastic or aluminium foil, and papers that are waxed, pasted, or gummed are usually not recycled because the process is too expensive. Gift wrap paper also cannot be recycled due to the its already low quality.

Import and export of recyclates

The value of recyclates can be seen by the fact that certain countries have begun to import the unprocessed materials. Some have complained that the ultimate fate of recyclates sold to another country is unknown and they may end up in landfill instead of reprocessed. Pieter van Beukering, an economist specializing in waste imports of People's Republic of China and India, believes however that it is unlikely that bought materials would merely be dumped in landfill. Instead, he claims that the import of recyclables allows for large-scale reprocessing, improving both the fiscal and environmental return through Economies of scale.

In some cases the cost of recycling is greater than the cost of putting garbage into a landfill. One example is the city of Santa Clarita, California which was paying $28 per ton to put garbage into a landfill. The city then adopted a diaper recycling program that cost $1,800 per ton.

All recycling techniques consume energy for transportation and processing and some also use considerable amounts of water, although recycling processes seldom amount to the level of resource use associated with raw materials processing.